It’s… garbage

Movie Reviews and Opinion by Nigel Tunstall

Reviews of recently released movies.

It’s… garbage

Prett-ay, prett-ay, prett-ay good

Personally, I was never particularly drawn to the quaintly simple ecosystem depicted in the Dune novels as, whilst we all know what deserts look like—or at least think we do—one that goes on for an entire planet, without an oasis, or a camel, or city to brighten the scene, seems kind of dull as far as settings go, and more than a tad implausible. The main narrative thread about a messiah also sticks in the craw if you think it’s dumb to believe in the supernatural.

That said, the universe imagined in the Dune novels is so vividly realized, you kind of forget these problems, and feel able to buy into the logic of the story. Moreover, some of the inventions—ornithopters, Sandworms, and Melange—are captivating, and highly original.

I read Dune—perhaps a third of it, anyway—maybe sixteen years after it was written, at a point (in 1981) when it was already regarded as a classic of science fiction, even if it seemed to have far more in common, thematically and in its overall “feel,” with fantasy.

I think the only real challenger, at that point, would have been The Lord of the Rings trilogy, which I’ve never read (because I don’t believe in dragons, or dwarves). None of these immensely popular books stands comparison to actual literature, like Tolstoy, Salinger, or F. Scott Fitzgerald. And, like Lilliputian hallucinations during an alcohol withdrawal, the tale struck me in adolescence as just as unbelievable as it does now.

Most of the world revels in garbage, though, which is why you can’t turn on the TV without seeing some of the sprawling fantasy series Game of Thrones—of which there are a staggering 73 episodes, made at an average cost of $15 million. I am guessing the scriptwriters were paid scale, based on the dialogue I’ve actually heard, which seems more like acting students improvising an argument about jousting technique between medieval knights than professional-level writing.

All of which brings me to Dune: Part Two. My main take-home is that it may not be as boring as Dune: Part One (2021). Fey, girly-looking actor Timothée Chalamet is a thing, I suppose, on account of the fact men are no longer allowed their Steve McQueens or Sean Connerys and, for me, he commands less screen presence than Clint Eastwood’s cigar smoke—but he is in fact cast as Paul Atreides and that is just what happened.

Like all contemporary blockbusters, it is often visually indistinguishable from a video game [see screenshot from the trailer at top]—though many scenes are so detailed and/or lifelike, I would guess more cash was lavished on its CGI than on that of any other movie in history—but, since you have less control over what you are watching, it’s also less immersive.

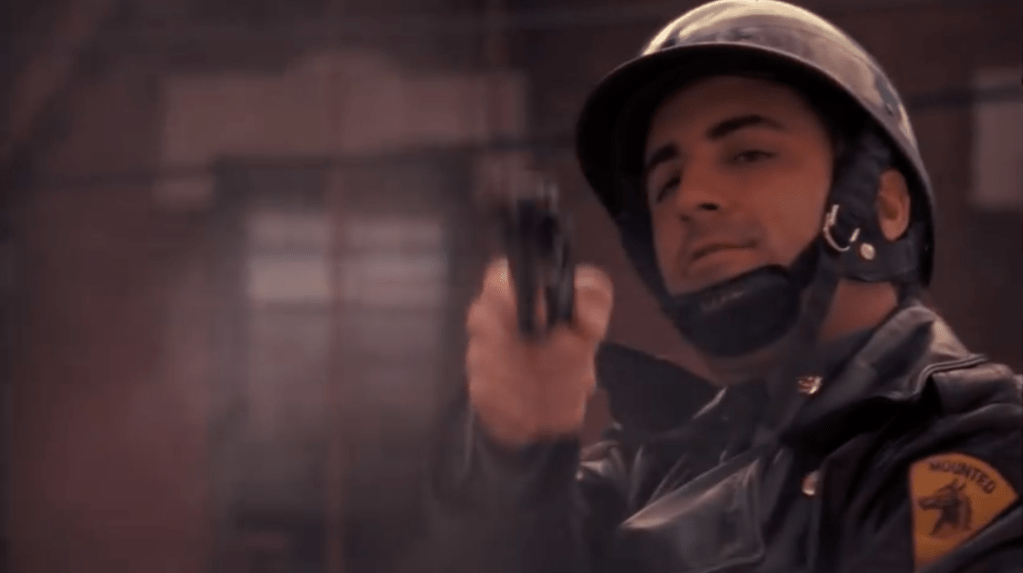

Javier Bardem overacts horribly as a sort of guru for the assembled quasi-Middle Eastern-accented Fremen, whilst Rebecca Ferguson and Austin Butler basically just show up and run through the motions. More generally, there are no good casting choices, with the exception of Christopher Walken, as the Emperor. He may have the most mesmerizing delivery of any living actor; but, he is wasted here. This is the fault of everyone from co-screenwriter Jon Spaihts—who churned out the logic-defying Alien offshoot Prometheus (2012)—to director and co-screenwriter Denis Villeneuve, whose output must rank as the most boring of any director in movie history. Here is his middle period of French Canadian fodder of unclear point:

In the period 1941-1950, John Huston made The Maltese Falcon, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, Key Largo, and The Asphalt Jungle. Between 1964 and 1971, Stanley Kubrick made Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, 2001: A Space Odyssey, and A Clockwork Orange. Most Hollywood movies made in the 1970s are superior to anything now being made by Hollywood, which is in its death throes.

Movies, on the other hand, will survive—but, if American dominance of the industry is to continue, then its center is going to have to relocate to Nevada, Texas, or Tennessee.

Hollywood is in a tailspin even Maverick would struggle to pull out of but, somehow, Tom Cruise is resurgent and keeping action filmmaking afloat, even amidst the debris of CGI and corporate woke blandness that is depleting Western culture to junk status. The landscape is in fact so bleak I am reviewing movies at the rate of about one per year.

The plot of Mission: Impossible—Dead Reckoning Part One is, naturally, another variation on the agent-must-stop-villain/weapon formula done best by the Bond series in its earliest (Sean Connery thru Roger Moore) phases; but, Ethan Hunt is less of a loner than Bond, and fully participates in team building with characters played by more charismatic actors, including Ving Rhames and Simon Pegg, while Rebecca Ferguson—attractive, but not so glamorous as to threaten Cruise’s ability to dominate the screen—is the token action woman. It rips off specific scene ideas from From Russia with Love (1963) and even The Godfather (1976), and has dialogue barely better than that of a typical TV movie, and lacking the warmth—but, nevertheless, keeps up an unrelenting pace, and in the action movie stakes outperforms the competing Fast and Furious series, coming second only to the other recent Cruise vehicle, Top Gun: Maverick (2022).

Cruise has less charisma than original TV series cast members Peter Graves’s or Greg Morris’s cufflinks, but has, amongst leading actors, unmatched ability to run and rapel, and ride, drive or fly anything with a motor—in an age where this sort of effect is most usually created on a computer—as well as hair of unsurpassed versatility. The only thing he can’t do with his body is walk tall, being 5′ 7″—but he fully looks the part in action sequences, and wisely steers clear of attempting Sean Connery-style seductions. The last movie I knowingly saw by director Christopher McQuarrie was Way of the Gun (2000), which was confusing and boring, and starred Ryan Phillippe, who is a mixture of the two qualities in human form.

Would you want a biopic about Elvis told from the perspective of “Colonel” Tom Parker? Probably not. Were you expecting it to be a 1950s “The Elvis Presley Story”-style film? Probably also negative. It seems to me that Elvis Presley is about the best-looking man who ever lived. Austin Butler, who portrays him here, is not. Neither can he move like Elvis, or project any sort of screen presence.

Director Baz Luhrmann, who started his career in blistering form with Strictly Ballroom (1992), sees Elvis more as a Bowie-like pop star who wears eyeliner and lipstick and always dresses in pink, which isn’t accurate. Elvis was undeniably a loud dresser, but had dark blonde hair before he started dyeing it black, which is perfectly obvious from early album covers. Distortions like these would surely be irritating to anyone with a basic familiarity with his biography.

Worse, the story is badly underdramatized, frequently deploys voice-over, and makes crude sociological points. If the internet has reduced your attention span to that of a gnat, however, this may be the movie for you. The crowded visual look and frenetic editing—which draw on close-ups, telephoto, zoom, dissolves, and match cuts, often all within a five-minute period—as well as overblown score, introduces a level of flamboyance that is quite un-called for, given the dazzling nature of the subject matter.

What is totally missing is restraint, or tonal contrast. I threw the towel in after forty minutes and used some of the time freed up to rewatch the start of Top Gun: Maverick, which looks like a work of genius in comparison to this piece of dreck.

Script conference, Paramount Pictures

“Describe Maverick’s character.”/“Well, he pushes the envelope. He’s an envelope-pusher.”/“Great—that’s our first scene, right there: Maverick pushing the envelope. What else?”/“Well, he’s a …maverick.”/“There’s our second scene! Oh, and put a bar in it like the one in The Right Stuff.”

Top Gun: Maverick is a beat-by-beat reproduction of the first film about trainee fighter pilots, in which Maverick (Tom Cruise) has to adapt to his new role as instructor. According to the Navy top brass, his record is distinguished, but they keep telling him how much they dislike him. That doesn’t actually make sense.

“Iceman” (Val Kilmer) is now admiral of the fleet, but they still call him “Iceman.” “Goose” is dead because in real life the actor playing him lost his hair. Maverick’s backstory is recapped by the bartender love interest (Jennifer Connelly), just in case we can’t keep up. A bespectacled nerd-flyer spills beer on his crotch to foreshadow having his pool cue taken away minutes later by a bully called Coyote.

Everyone here is THE BEST THERE IS, which is the same as saying they’re nothing special. The twist is there is a woman in the batch, although she is demoted to background and forgotten about quickly, and for the rest of the movie. Training under Maverick consists, during the very first session, of going from no combat training to mock dogfights flown at very low level and going over your emotional baggage while spiralling downward toward the desert.

Tom Cruise has two acting modes—jubilant, and confused (probably representing deep emotion). There is nothing between these extremes. The tone here is mordant until the third act, though, so he never really breaks out of confused mode.

Director of the first movie Tony Scott jumped to his death from Golden Gate Bridge so wasn’t available to direct this one, but they copied his visual style, which includes much sunlight on tarmac and streaming through blinds onto the sides of faces, somewhat laboriously. Several scenes from the original are reproduced in their entirety.

This is movie-making by committee. Most of the dialogue is stolen from other movies, including a gratuitous “Don’t break her heart.” What Top Gun: Maverick has going for it is the action sequences, which look better than those of any other—even Tom Cruise movies—but its 2h 11m running time and downbeat tone dull your enjoyment. The only piece conspicuously missing from the jigsaw is a memorable power ballad.

I got through almost 90 minutes of this before realizing it was more important to get on with the rest of my life—particularly since, if you want to do a tour of the British Museum on sedatives, you don’t need to spend $165 million.

Canadian—“French Canadian,” as IMDb dutifully points out—director Denis Villeneuve does another in his series that answers a question no one asked: How would Ridley Scott have shot this? Neither did I make it through the last ditchwater-dull iteration, Blade Runner 2049 (2017).

The reason, of course, is that you can’t stare at a screen for 2h 35min and remain interested unless there is also interesting dialogue, characters, and acting, of which this has none. It suffers from the same general problem all Cecil B DeMille movies show—portentous, self-important dialogue that bears no relation to the way people actually speak. The anesthesia induction palm itself off as the introduction to a movie contains not a single line of realistic dialogue—and there is no way of relating to the various assembled practitioners of feudal etiquette or escrima.

As you might expect, the space hardware is okay, in a familiar, XBox One sort of way—if you don’t mind the occasional steal from 2001: A Space Odyssey and Star Wars—and its ornithopters look persuasively flyable, in a Desert Storm sort of way… but you can’t be expected to watch a movie on that basis, any more than spend three hours in a Toyota showroom.

Like most science-fiction, it appeals more to the intellect than the heart—and there are just not enough ideas at play to make it interesting.

By contrast, David Lynch’s baroque, incoherent, and at times disgusting 1984 version had the great merit of seeming genuinely alien.

Going to see another Marvel movie makes me feel like a housewife returning to the same drunken pig for yet another beating. This movie—if you can even apply the word in this case and believe it’s really the same type of thing as To Have and Have Not or On the Waterfront—must be among the dullest ever produced.

And produced is the operative work—it looks and feels to be exactly what it is: a composite work of digitalised celluloid Lego with all the lustre of a term paper on why wokeness is just more white privilege. There is not a single line of dialogue that resembles how people actually speak, and the march to diversify is in this instance embodied by some void in the English Stage Acting mode, like they thought reverting to a time before great movie acting was an ace move.

It’s another pay check call for Scarlett Johansson in a career that at this point looks astonishingly complacent, and lucky—even if she evinced a nicely understated, touchingly guileless impression in Ghost World and Lost In Translation, and was one of very few actors resembling a movie star from the Golden Age who could also act. Aside from the hardware of Johansson herself—and she is not shown here to her best advantage in any way, shape, or form, being fully dressed in a leather motorcycle one-piece throughout—the best realised aspect of Avengers #who knows? is futuristic super-planes.

Everything else is spinning kicks and well-executed parries, but without feeling. I am sure I have seen her do very decent-looking fight scenes before—but, here, you might as well be watching gameplay of Mortal Kombat, it’s that unconvincing, if slick.

Which is my point, I think, if I have one: reality is messy so, without light and shade, and things going wrong some of the time, you have no way of relating to what’s onscreen.

I am not sure I can even say anything about the plot—I had literally no bearings for what I was watching other than a vague recollection of seeing Johannson in some previous Avengers-type snooze-a-rama—so we’re not going to talk about it. What I can say is that there there are a lot of Russians—purported Russians, really—one of them being Ray Winstone, who has the decency to do a technically proficient acting job.

If super heroes have super powers, Black Widow’s seem to be advanced level kickboxing, and ability to fire Imperial Storm Trooper Mogadon-overdose laser bolts from her wrists. If she is a spider of some kind, I’m a banana.

So, it may be more productive briefly to review the careers of these two stars—kind of star, in the case of Winstone, if you count starring roles in movies no one saw and character bits in major releases. Let’s rank their respective outputs.

Actually, that would take way too long, so let’s go with my highly edited version.

Scarlett Johannson

The Man Who Wasn’t There (2001) Don’t even recall her being in this but, in the current spirit of grade inflation, let’s give her an A*

Ghost World (2001) A* again

Lost in Translation (2003) A*—not bad, so far

Match Point (2005)—I might have to look at this again, but as I recall one of the few watchable elements in one of many Woody Allen nadirs

The Island (2005)—Uh, I don’t completely remember, but wasn’t this garbage? Let’s say B+, just to be charitable.

The Black Dahlia (2006) A

Vicky Cristina Barcelone (2008) B

Iron Man 2 (2010) You can’t really even see anyone else on-screen when the luminescent Robert Downey, Jr. is in a scene, but probably B+, rising to an A on appeal

Lucy (2014) B+

…And literally everything since has been a stream of crap.

Ray Winstone

Scum (TV movie, 1979) A* before anyone was awarded one

Nil by Mouth (1997) A*

Sexy Beast (2000) A*

Ripley’s Game (2002) A-

The Departed (2006) A

Beowulf (2007) F—if you can call this kind of CGI horseshit acting

King of Thieves (2018) C-

Conclusion

Both are poster people for selling out, but Winstone edges it based on heart.

F9: The Fast Saga (AKA Fast & Furious 9, or just F9) contains no more than a few minutes of verisimilitude—which I suppose is fine if your target audience’s reality is spending 16 hours a day playing Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas and huffing lighter fuel.

So, the art of motion pictures has developed from an initial rudimentary level through innovation and improvisation brought about by successive geniuses like Eisenstein, Hitchcock, Kubrick, Roeg, Scorsese and Tarantino—much like how jazz or blues musicians expanded on what came before, to produce something new and better.

Somewhere along the way, post-Lucas and Spielberg, Hollywood was taken over by dopes in suits who determined that we don’t need story-telling—or reality at any level—and that the way to make movies was to to fill them end-to-end with action sequences so absurd you could not even consider suspending your disbelief, and break it up every thirty minutes or so with scenes of wooden expository dialogue.

The plot of this monstrosity, as far as I can discern one, is a macho intra-familial type thing about redemption and intimidating your first-degree relatives by taking steroids and driving fast in Costa Rica, Bangkok, and Outer Space.

Fast & Furious stalwart Vin Diesel has a certain kind of low-key charisma, but deploys an expression I’ve only ever seen used onscreen by Tom Cruise or, in real life, people recovering from enemas. I imagine it is intended to convey deep emotion. In terms of range, he makes Sylvester Stallone look like Meryl Streep.

John Cena and Lucas Black are so ugly they would not have been cast in movies made earlier than 1980, except as extras in Hammer Horror flicks—while acting bot Charlize Theron is here too alien, like she based her performance on Michael Fassbender’s in Prometheus, in which they co-starred. Either way, she looks and acts weird. Helen Mirren seems to have based her accent on Dick Van Dyke’s in Mary Poppins, and her performance is the only true embarrassment in her career I am aware of.

The only naturalistically acted scene features Kurt Russell, looking like he is in a completely different film. The actor who emerges with the most credit is Ludacris, who has a comedy pairing with the god-like Tyrese Gibson; but they struggle with the unfunny dialogue and ridiculous scenario. It’s …garbage.

Coppola has previously copped to his motivation for making the Godfather: Part III: a need for cash—specifically, his family’s—which is fair enough, as far as it goes.

In making it, however, he produced the most shocking piece of crap he’d ever made, and ruined a rich seam of filmic gold that began with The Godfather—itself a surprising act of alchemy that turned a superior work of pulp fiction into an exciting and deceptively cerebral movie through sublime and nuanced dialogue, acting, and cinematography.

The reality of the American Mafia—or criminality generally, for that matter—is nothing like the world depicted in The Godfather, which is more like a bunch of corporate suits plotting the takeover of a rival bank, though with more danger of being rubbed out on the causeway—but that was what Coppola intended, as he felt he was satirizing capitalism.

In any case, The Godfather and The Godfather: Part II have a coherent internal logic that makes it all seem real—unlike the Godfather: Part III, which entails a collision of mismatched styles and themes and nothing much in the way of narrative. The dialogue is among the worst you could expect to encounter in the genre, viz:

You know, Michael, now that you’re so respectable I think you’re more dangerous than you ever were. In fact, I preferred you when you were just a common Mafia hood.

[Diane Keaton]

If someone is going around this city saying, “F— Michael Corleone,” what do we do with a piece of s— like that? He’s a f—ing dog.

[Al Pacino]

Yes, it’s true. If someone were to say such a thing, they would not be a friend. They would be a dog.

[Joe Mantegna]

…and so on, and on.

A few action scenes are handled quite well—Andy Garcia blowing out the brains of some hoodlums who have been sent to assassinate him, or his baroquely engineered slaying of Joe Montagna from horseback, dressed as an NYC cop. Both scenes look great, but neither makes any sense if you have the presence of mind to think for a millisecond about what is going on.

The only other highlight is Bridget Fonda—appearing mostly with Andy Garcia, as it happens—and the less said about Sofia Coppola, the void playing Al Pacino’s son, or even Pacino, the better.

Most of the location work looks like video of a House and Garden magazine shoot, and the denouement may, for all I know, appeal to opera lovers, but looks like it was accidentally intercut by a trainee editor who’d never seen a motion picture.

The Godfather Coda: The Death of Michael Corleone cannot eradicate these inexplicable choices, but this re-edit gives the narrative a modicum of coherence, even if it remains dull as ditchwater. Weirdly, the whole thing is prefaced by a straight-to-camera by Coppola that invites obvious satire along the lines of The Death of Francis Ford, but you just wish he’d made anything other than this movie.

My version would have killed off Michael Corleone early on—replacing the ridiculous pseudoseizure-flashback-stroke scene with a firefight—focused on Garcia’s and Fonda’s characters’ relationship, and explored the pitfalls of falling for a good-looking psychopath (perhaps ending with a heroin overdose)—but unfortunately no one asked me.