Personally, I was never particularly drawn to the quaintly simple ecosystem depicted in the Dune novels as, whilst we all know what deserts look like—or at least think we do—one that goes on for an entire planet, without an oasis, or a camel, or city to brighten the scene, seems kind of dull as far as settings go, and more than a tad implausible. The main narrative thread about a messiah also sticks in the craw if you think it’s dumb to believe in the supernatural.

That said, the universe imagined in the Dune novels is so vividly realized, you kind of forget these problems, and feel able to buy into the logic of the story. Moreover, some of the inventions—ornithopters, Sandworms, and Melange—are captivating, and highly original.

I read Dune—perhaps a third of it, anyway—maybe sixteen years after it was written, at a point (in 1981) when it was already regarded as a classic of science fiction, even if it seemed to have far more in common, thematically and in its overall “feel,” with fantasy.

I think the only real challenger, at that point, would have been The Lord of the Rings trilogy, which I’ve never read (because I don’t believe in dragons, or dwarves). None of these immensely popular books stands comparison to actual literature, like Tolstoy, Salinger, or F. Scott Fitzgerald. And, like Lilliputian hallucinations during an alcohol withdrawal, the tale struck me in adolescence as just as unbelievable as it does now.

Most of the world revels in garbage, though, which is why you can’t turn on the TV without seeing some of the sprawling fantasy series Game of Thrones—of which there are a staggering 73 episodes, made at an average cost of $15 million. I am guessing the scriptwriters were paid scale, based on the dialogue I’ve actually heard, which seems more like acting students improvising an argument about jousting technique between medieval knights than professional-level writing.

All of which brings me to Dune: Part Two. My main take-home is that it may not be as boring as Dune: Part One (2021). Fey, girly-looking actor Timothée Chalamet is a thing, I suppose, on account of the fact men are no longer allowed their Steve McQueens or Sean Connerys and, for me, he commands less screen presence than Clint Eastwood’s cigar smoke—but he is in fact cast as Paul Atreides and that is just what happened.

Like all contemporary blockbusters, it is often visually indistinguishable from a video game [see screenshot from the trailer at top]—though many scenes are so detailed and/or lifelike, I would guess more cash was lavished on its CGI than on that of any other movie in history—but, since you have less control over what you are watching, it’s also less immersive.

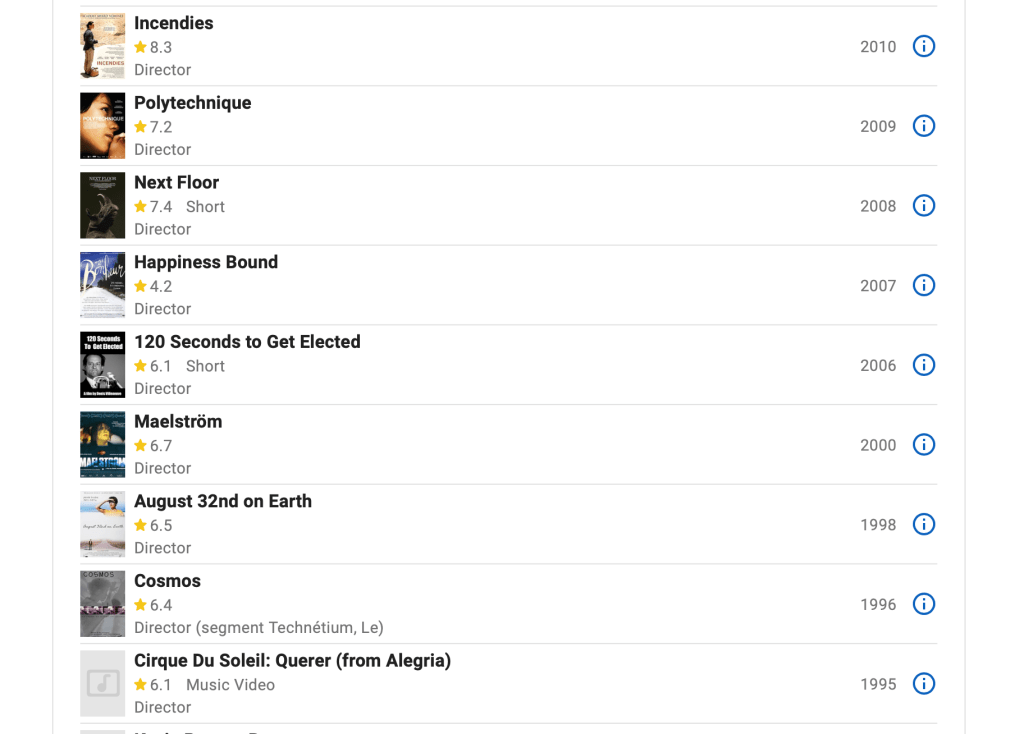

Javier Bardem overacts horribly as a sort of guru for the assembled quasi-Middle Eastern-accented Fremen, whilst Rebecca Ferguson and Austin Butler basically just show up and run through the motions. More generally, there are no good casting choices, with the exception of Christopher Walken, as the Emperor. He may have the most mesmerizing delivery of any living actor; but, he is wasted here. This is the fault of everyone from co-screenwriter Jon Spaihts—who churned out the logic-defying Alien offshoot Prometheus (2012)—to director and co-screenwriter Denis Villeneuve, whose output must rank as the most boring of any director in movie history. Here is his middle period of French Canadian fodder of unclear point:

In the period 1941-1950, John Huston made The Maltese Falcon, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, Key Largo, and The Asphalt Jungle. Between 1964 and 1971, Stanley Kubrick made Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, 2001: A Space Odyssey, and A Clockwork Orange. Most Hollywood movies made in the 1970s are superior to anything now being made by Hollywood, which is in its death throes.

Movies, on the other hand, will survive—but, if American dominance of the industry is to continue, then its center is going to have to relocate to Nevada, Texas, or Tennessee.