Coppola has previously copped to his motivation for making the Godfather: Part III: a need for cash—specifically, his family’s—which is fair enough, as far as it goes.

In making it, however, he produced the most shocking piece of crap he’d ever made, and ruined a rich seam of filmic gold that began with The Godfather—itself a surprising act of alchemy that turned a superior work of pulp fiction into an exciting and deceptively cerebral movie through sublime and nuanced dialogue, acting, and cinematography.

The reality of the American Mafia—or criminality generally, for that matter—is nothing like the world depicted in The Godfather, which is more like a bunch of corporate suits plotting the takeover of a rival bank, though with more danger of being rubbed out on the causeway—but that was what Coppola intended, as he felt he was satirizing capitalism.

In any case, The Godfather and The Godfather: Part II have a coherent internal logic that makes it all seem real—unlike the Godfather: Part III, which entails a collision of mismatched styles and themes and nothing much in the way of narrative. The dialogue is among the worst you could expect to encounter in the genre, viz:

You know, Michael, now that you’re so respectable I think you’re more dangerous than you ever were. In fact, I preferred you when you were just a common Mafia hood.

[Diane Keaton]

If someone is going around this city saying, “F— Michael Corleone,” what do we do with a piece of s— like that? He’s a f—ing dog.

[Al Pacino]

Yes, it’s true. If someone were to say such a thing, they would not be a friend. They would be a dog.

[Joe Mantegna]

…and so on, and on.

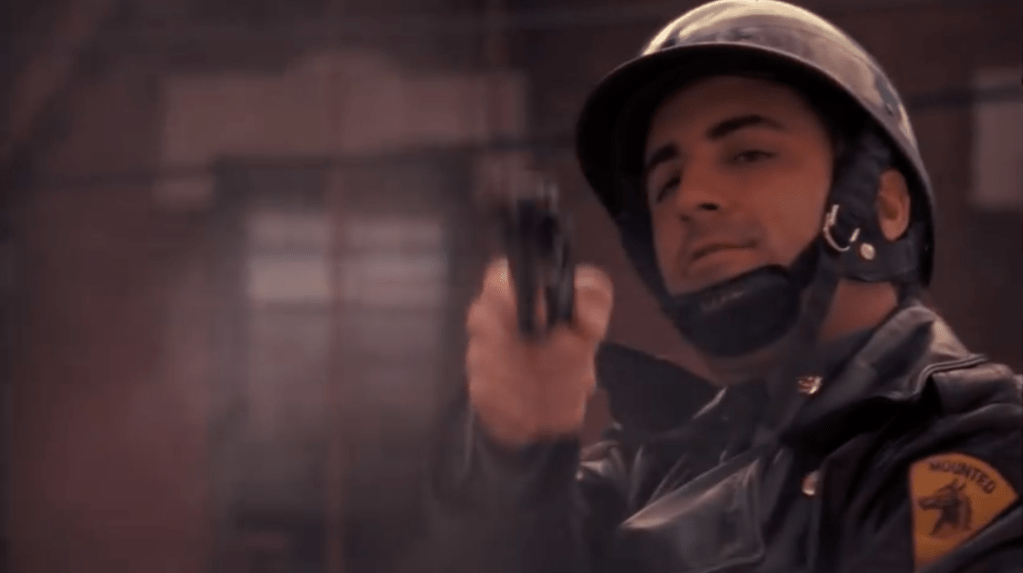

A few action scenes are handled quite well—Andy Garcia blowing out the brains of some hoodlums who have been sent to assassinate him, or his baroquely engineered slaying of Joe Montagna from horseback, dressed as an NYC cop. Both scenes look great, but neither makes any sense if you have the presence of mind to think for a millisecond about what is going on.

The only other highlight is Bridget Fonda—appearing mostly with Andy Garcia, as it happens—and the less said about Sofia Coppola, the void playing Al Pacino’s son, or even Pacino, the better.

Most of the location work looks like video of a House and Garden magazine shoot, and the denouement may, for all I know, appeal to opera lovers, but looks like it was accidentally intercut by a trainee editor who’d never seen a motion picture.

The Godfather Coda: The Death of Michael Corleone cannot eradicate these inexplicable choices, but this re-edit gives the narrative a modicum of coherence, even if it remains dull as ditchwater. Weirdly, the whole thing is prefaced by a straight-to-camera by Coppola that invites obvious satire along the lines of The Death of Francis Ford, but you just wish he’d made anything other than this movie.

My version would have killed off Michael Corleone early on—replacing the ridiculous pseudoseizure-flashback-stroke scene with a firefight—focused on Garcia’s and Fonda’s characters’ relationship, and explored the pitfalls of falling for a good-looking psychopath (perhaps ending with a heroin overdose)—but unfortunately no one asked me.